Cover Story

Breakthroughs in DVT Treatment

By Jennifer Boggs | Feature

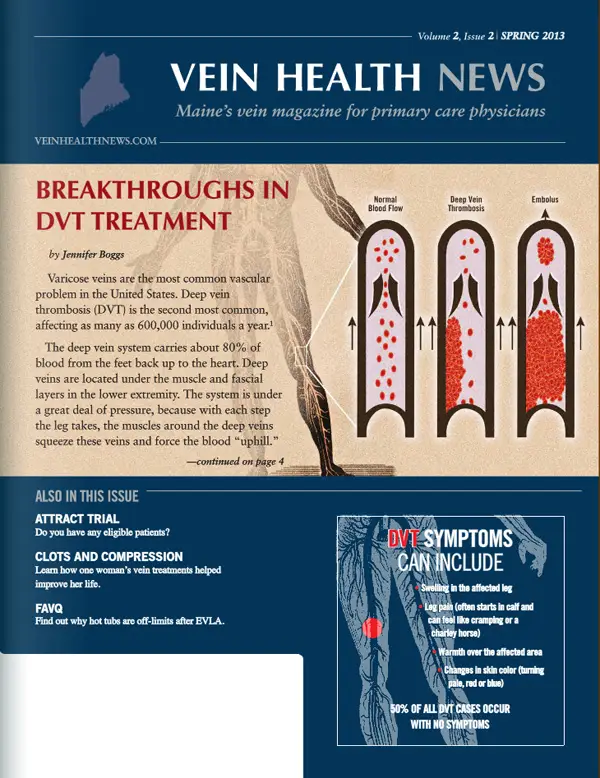

Varicose veins are the most common vascular problem in the United States. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is the second most common, affecting as many as 600,000 individuals a year.

The deep vein system carries about 80% of blood from the feet back up to the heart. Deep veins are located under the muscle and fascial layers in the lower extremity. The system is under a great deal of pressure, because with each step the leg takes, the muscles around the deep veins squeeze these veins and force the blood "uphill."

Of course, the danger of DVT is that the high pressure in the deep vein system could cause the clot to break free from the vein wall and enter into the blood stream. The clot would then travel up through the legs, through the major vessels in the abdomen, and into the vena cava and into the right atrium. If the clot follows normal circulation, it would enter the right atrium and move to the right ventricle and then be pumped to the lungs. Once in the lungs, it would be a pulmonary embolism (PE), which can be symptom-free and/or fatal, depending upon the size and location of the clot.

If the heart has any wall defects—a condition likely found in more than 25% of patients—the clot could cross to the left side of the heart and then be pumped to the brain instead of the lungs, resulting in stroke. If the clot doesn't move, there are still other risks to consider, including Post-Thrombotic Syndrome (PTS). In fact, 40% of patients who have had DVT will have some degree of PTS, and in 4%, severe PTS will develop.

Early detection and education

According to Dr. Paul Kim, the key to treating DVT—and possible prevention of PTS—is early detection. Dr. Kim, the Assistant Director of Vascular and Interventional Radiology at Maine Medical, believes that primary care physicians should be attentive to the classic symptoms of DVT: sudden onset of leg pain and/or swelling. "The more aware doctors are of DVT as a possible cause of symptoms, the more quickly they can take action," he said.

Other symptoms include leg fatigue, tenderness, warmth in the skin, and redness or discoloration of the skin. In half of DVT cases, no symptoms present at all. DVT is a medical emergency, so any of these symptoms should be regarded as a DVT until proven otherwise, especially if someone is in a risk category.

If a physician suspects a DVT in the lower extremities, the first step toward an accurate diagnosis is an ultrasound. Dr. Kim recommends a three-point compression technique, in combination with a duplex ultrasound, which can "give additional information about the severity of the blood clot." The three-point compression technique concentrates on the evaluation of those areas with highest turbulence and at greatest risk for developing thrombus: 1) the common femoral vein at the saphenous junction, 2) the femoral and deep femoral veins, and 3) the popliteal vein. Research has suggested that the three-point compression technique allows physicians to determine within several minutes and with 98% correlation with the duplex ultrasound examination the presence or absence of lower extremity DVT.

According to Dr. Kim, early detection not only remedies the patient's acute pain, but also reduces the risk of potentially fatal PEs. The DVT itself could cause a chronic problem that inhibits quality of life, or even a patient's ability to work. "Even though DVT can be a lifetime disease, it's a leg issue that's sometimes forgotten," said Dr. Kim. "The sooner we can detect and treat it, however, the more likely we can eliminate the DVT."

ATTRACT

For the last half-century, doctors have by and large treated DVT with anticoagulation therapy, most often unfractionated heparin (administered intravenously), a low molecular weight heparin (injected), warfarin (taken orally), or fondaparinux (injected), given for at least 5 days following diagnosis. Anticoagulant drugs prevent further clots from forming, as well as diminish the risk of a PE. However, anticoagulant medications do not actively eliminate the DVT. Consequently, PTS occurs frequently in anticoagulated DVT patients.

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) in the ninth edition of The Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, encourages physicians to consider all the options. One option is pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis (PCDT), which delivers a "clot-busting" drug (a tissue plasminogen activator, or tPA) directly into the blood clot through a specially designed catheter (plastic tube) or catheter-mounted device that may also break up the clot and/or remove the clot fragments. It is a minimally invasive procedure done while the patient is under sedation. The results are rapid, with most patients experiencing significantly relief from pain and swelling within 48 hours.

ATTRACT—Acute venous Thrombosis: Thrombus Removal with Adjunctive Catheter-directed Thrombolysis is a $10.3 million study sponsored by the National Institutes of Health that is evaluating the use of this technique. Maine Medical Center is one of 35 centers in the U.S. chosen to participate in the clinical trial, and Dr. Kim is serving as principal investigator.

"So far, this kind of clot removal therapy has been promising in improving the acute symptoms, but also improving symptoms of PTS," he said. "The idea is if we can catch it sooner and remove the clot faster, we reduce the risk of valve damage."

Dr. Kim added that PCDT is not a new treatment and has been available for nearly two decades; he and his colleagues have used the treatment with more than one hundred patients over the last several years. The ATTRACT study is, however, a new way to figure out where exactly its benefits lie and whether it should become the standard of care or be reserved for specific cases, as these procedures may involve more bleeding risks and use of hospital resources. It is the first and only randomized controlled study looking at PCDT vs. anti-coagulation alone.

INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION CRITERIA FOR ATTRACT STUDY

ATTRACT INCLUSION CRITERIA:

- Symptomatic proximal DVT involving the iliac, common femoral, and/or femoral vein.

- No previous symptomatic DVT within the last 2 years.

- In the contralateral (non-index) leg: symptomatic acute DVT a) involving the iliac and/or common femoral vein; or b) for which thrombolysis is planned as part of the initial therapy.

ATTRACT EXCLUSION CRITERIA:

- Age less than 16 years or greater than 75 years.

- Symptom duration > 14 days for the DVT episode in the index leg (i.e., non-acute DVT).

- In the index leg: established PTS, or Limb-threatening circulatory compromise.

- PE with hemodynamic compromise (i.e., hypotension).

- Inability to tolerate PCDT procedure due to severe dyspnea or acute systemic illness.

- Allergy, hypersensitivity, or thrombocytopenia from heparin, rt-PA, or iodinated contrast, except for mild-moderate contrast allergies for which steroid pre-medication can be used.

- Hemoglobin < 9.0 mg/dl, INR > 1.6 before warfarin was started, or platelets < 100,000/ml.

- Moderate renal impairment in diabetic patients (estimated GFR < 60 ml/min) or severe renal impairment in non-diabetic patients (estimated GFR < 30 ml/min).

- Active bleeding, recent (< 3 mo) GI bleeding, severe liver dysfunction, bleeding diathesis.

- Recent (< 3 mo) internal eye surgery or hemorrhagic retinopathy; recent (< 10 days) major surgery, cataract surgery, trauma, CPR, obstetrical delivery, or other invasive procedure.

- History of stroke or intracranial/intra spinal bleed, tumor, vascular malformation, aneurysm.

- Active cancer (metastatic, progressive, or treated within the last 6 months). Exception: patients with non-melanoma primary skin cancers are eligible to participate in the study.

- Severe hypertension on repeated readings (systolic > 180 mmHg or diastolic > 105 mmHg).

- Pregnant (positive pregnancy test, women of childbearing potential must be tested).

- Recently (< 1 mo) had thrombolysis or is participating in another investigational drug study.

- Use of a thienopyridine antiplatelet drug (except clopidogrel) in the last 5 days.

- Life expectancy < 2 years or chronic non-ambulatory status.

- Inability to provide informed consent or to comply with study assessments.

Managing DVT

Among patients who have had a DVT, one-third experience post-thrombotic syndrome and about one-third will have a recurrence of DVT within 10 years. Chronic problems for DVT patients can include venous insufficiency, heaviness and swelling—symptoms similar to insufficiency in the superficial venous system. The difference, according to Dr. Kim, is that superficial venous insufficiency can be treated, but "there is no FDA-approved treatment for deep venous insufficiency, besides compression stockings and supportive care."

Patients with DVT should wear graduated compression stockings on a daily basis, since several studies strongly suggest that their use can significantly reduce the likelihood of the patient developing PTS. In fact, according to the recommendations by the ACCP, wearing compression stockings reduces the incidence of post-thrombotic syndrome by half when worn for two years following DVT.

In addition to managing both acute and chronic DVT, compression can be a tool for prevention. When there are risk factors for DVT, such as long distance car or plane travel, immobility, or pregnancy, wearing compression can reduce its occurrence. Dr. Kim recommends a 30-40mmHg strength compression (gradient compression is expressed in millimeters of mercury, or mmHg) to all his DVT or venous insufficiency patients. Despite the relief of symptoms that patients experience when wearing compression, Dr. Kim admits that the issue of patient compliance can be "tough."

Communication

Patient Communication: Room for the Unknown

By Helane Fronek, MD, FACP, FACPH

Physicians are often placed in the daunting role of expert. Our patients come to us when they have difficulties and expect that we will figure out what's wrong and tell them what to do about it. Fortunately, we do know a lot. We attend school, training programs, ongoing CME, read continuously, and communicate with our colleagues to stay abreast of the newest developments and obtain other perspectives on our difficult cases. We work hard to know what we know. But if we're honest with ourselves, we will admit that there's probably more that we don't know.

Consider some of the things you were taught during your training that are now known to be false. How much of what we now believe is true will be proven wrong in the future? So why do we hold onto this illusion that we know—and are supposed to know—everything? Each patient we treat has a slightly different situation; perhaps their condition is more severe or complicated by other concomitant illnesses. Or, one patient may have an unexpected reaction to a medication we prescribe, because of inborn differences in processing of certain drugs, or because they are taking another medication. And then there is the issue of patient adherence to our recommendations.

In spite of all of these unpredictable variables, we are still surprised when the outcome of our intervention isn't what we expected. It makes most of us uncomfortable. We often try to explain away the poor result and sometimes blame the patient: our patient did not wear her stockings as we requested. Or, he exercised too vigorously after the treatment.

I recently saw a frustrated patient who had a poor result to treatment. Five months after endovenous thermal ablation and ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy of her great saphenous vein and tributaries, she continued to experience pain in her leg, swelling in her ankle, and persistent pigmentation of her skin. She was labeled "difficult" as she spent visit after visit complaining. Unable to wear compression stockings because of allergic rashes that developed each time she put one on, she was considered "non-compliant."

The first thing we did was to express our agreement with her assessment—this was not the result she or the physician had wanted. Then, we took a fresh look at her. With a careful ultrasound, we found that a section of her great saphenous vein had not closed completely and reflux was noted in this segment, extending into tributaries in the calf where her pigmentation was quite visible. When we explained what we saw, she wondered why no one had told her this before. When we suggested that perhaps a cotton stocking might solve her compression woes, she questioned why that had not been suggested.

While I can imagine many reasons—the physician's own discomfort with a poor response, an inability to explain the failure, frustration with the demands of the patient—the lack of honesty and a thorough evaluation of her concerns did more harm to the relationship than the unsatisfactory result did. Many years ago, I treated a complex patient who had undergone coil embolization and sclerotherapy of her ovarian and iliac veins for pelvic congestion syndrome. She was "60% better" but wished to have the remaining painful calf varicosity treated. Her anatomy was complicated and unusual and, it turned out, her varicosities extended through the substance of her sciatic vein. With one injection, I caused her to have a foot drop as the sclerosant irritated the distal sciatic and peroneal nerves.

At the time, I had no idea why this had occurred – and I told her that. But I assured her that I would do my best to find out what happened and to help her recover as much function as possible. With the help of an astute neurologist, we made the diagnosis and she began a slow and unsure recovery. An avid runner, my patient's foot drop created a significant, negative impact on her daily life. However, she understood that much of what medicine does is unknown, that she would be informed as new information came to light, that her recovery was important to me as well as to her, and that she had not been abandoned. Rather than bringing a malpractice suit, she brought gifts and thank you notes.

So, yes, our patients expect us to be experts. But more importantly, they expect us to carefully evaluate their concerns, communicate clearly about what they have, and use our knowledge and experience to attempt to make them better. When our knowledge falls short, our patients are usually accepting if they see that we are honest, concerned, and will stay by their side as we seek more information to explain and improve their condition, or as they adjust to a new status.

Patient Perspective

One Patient's Perspective: Exploring Options

By Benjamin Lee

Lisa Freeman has been dealing with blood clots and compression stockings since she was 17 years old. When her doctors discovered clots in both legs the first time, ultrasound sonography wasn't widely used, as it is now. Freeman had a venogram, in which x-rays were taken after a contrast dye was injected into the distal parts of her legs and tourniquets were placed at various spots on each leg. She described the process as "awful and archaic."

Freeman was given clot-dissolving medication and put on bed rest (again, outdated advice, since now patients are encouraged to get up and move, if they're able). She was discharged with Coumadin and compression stockings, and while she took the medication faithfully, as a college student the stockings didn't "fit in with [her] routine or image." After taking warfarin for one year, Freeman stopped and was promptly hospitalized again with blood clots. Although this time she wore the compression stockings more often, she thought it was more for her comfort, not for actual treatment or prevention.

Several years later, Freeman developed venous ulcers. That scared her enough so that she became "religious" about wearing compression. "Before I sought help for my veins, I would put on the knee-high stockings first thing in the morning, even if I was just making breakfast before getting in the shower."

Now 45 years old and a medical-surgical nurse, Freeman is on her feet all day and continues to cope with her leg problems. It affects her endurance, so she can't work her 12-hour shift three days in a row. About a year ago, Freeman went to a free vein screening and came away surprised—and elated. She said she almost didn't believe the physician when she heard about the possible treatments.

"I had no idea that the symptoms I was experiencing, like itching and swelling, were related to venous insufficiency, and I didn't know there was anything you could do for veins," said Freeman. She and the vein specialist talked about her goals to increase endurance and relieve leg pain. They agreed on a plan to do endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) on her left leg and then, eventually, on her right leg. It has been about eight months since Freeman has had the EVLA procedure on her left leg and she is well on her way toward her goals of increased endurance and less pain.

Despite the fact that when she was 30, Freeman "gave up caring about what her legs looked like," the vein treatment has had an added benefit: "You can see the shape of my leg again!" In the 25 years Freeman dealt with blood clots and leg pain, she had never been asked about her veins or how her venous issues affected her quality of life. While doctors have handled her acute management and Coumadin dosages, she was never told about the procedures that are available.

"I never thought there was anything that people could do for veins, so to learn that there was a physician who specialized in it: suddenly there were options," said Freeman. "Finding out your options is a great starting point."

FAVQ

Are there any restrictions after an EVLA procedure?

By Dr. Cindy Asbjornsen

Are there any restrictions after an EVLA procedure?

In my practice I suggest three restrictions after Endovenous Laser Ablation (EVLA): no heavy lifting, no strenuous physical activity while standing, and no hot tubbing. The main reason for the first two restrictions is that those activities increase intra-thoracic pressure—that is, by tightening the core or abdominal muscles—and pressure downward into the legs is increased. That pressure can cause irritation of the treated vein which leads to swelling, which then turns into phlebitis. The closed vein likely won't open, but a high thigh phlebitis can be quite uncomfortable.

Patients should feel free to exercise, as long as their feet remain at, or above, the level of the heart (e.g. swimming or floor exercises, ideally with feet on an exercise ball). In fact, walking 30 minutes a day is a post-op requirement. Walking causes rhythmic calf contractions, which force the blood back up to the heart in the deep vein system, taking the pressure away from the superficial system that was just treated.

Hot tubs are a restriction because even though we sometimes suggest patients use heating pads post-procedure, in a hot tub all of the veins in the legs above and below the treated area become dilated. This can actually cause pain. Post-procedure requirements are as important as restrictions. The most important requirement is for patients to wear graduated compression stockings. As with any treatment, patients who follow the guidelines for care help promote the most effective healing.

What is the value of compression, pre- and post- procedure?

Before the procedure, wearing compression stockings gives the patient a snapshot of what vein health feels like. Since compression alleviates symptoms, it becomes easier to tease out (or confirm) whether the leg pain is due to muscular-skeletal issues, the nervous system, or venous disease.

Another benefit to wearing compression prior to treatment is that it's good to confirm that the patient can tolerate stockings, and/or that the stockings fit properly. After the procedure is the worst time to discover that the stockings don't fit or are not tolerated because of comfort. Alternatively, many people who thought that they could never tolerate compression stockings try on a modern stocking and find them quite bearable. Since compression prevents the progression of vein disease and controls symptoms, some patients may decide to take a more conservative approach, rather than proceed with definitive treatment.

Gradient compression after EVLA has been proven to prevent swelling, a common complication. Additional benefits for the patient are decreased discomfort, potentially decreased risk of blood clots, and potentially decreased risk of pigmentation. Compression is critical for the most efficient and effective healing process.

Vein Tech

Ezy-As

By Jennifer Boggs

There are many benefits to compression—but patients will receive none of them if they can't get their compression garments on. A compression garment applicator called Ezy-As aims to help. Ezy-As is a cylinder-shaped device that removes the elasticity from the garment during application, making it easier to get over the foot and ankle, while preserving the garment's efficacy.

The applicator fits compression garments to both lower and/or upper limbs and can be used with a variety of stockings: open- or closed-toe, knee-high or full leg. Patients can use it on themselves, or someone else can assist them if they are unable to "load" the stockings on the device on their own. Once the garment is properly placed on the applicator, it should take seconds to don.

The first Ezy-As applicator was created by a farmer named Barry Hildebrandt, Sr. in Queensland, Australia. After Hildebrandt was in a motorcycle accident that caused some lower limb complications, he was required to wear a compression garment on a regular basis. Hildebrandt knew firsthand the problems faced by patients while donning a compression garment, and it was those difficulties that led him to design the Ezy-As. Using his farming knowledge and can-do attitude, he started experimenting with various designs.

After several prototypes, the Ezy-As product was born in 2006, along with the company. In 2007, the applicator won the top prize on an Australian TV show called "New Inventors." The following year, Ezy-As won the "Next Big Thing" award, further establishing the product in Australia and beyond. Sales grew domestically and now the Ezy-As is available through distributors in the US and UK.

Orthotic clinicians Stephen Dickins and Tim Jarrott are the current owner/directors of the Ezy-As business, which is based in Melbourne, Australia. According to Dickins, Ezy-As decreases the exertion and bending required for donning lower limb garments, in particular. "Ezy-As was designed with compression therapy users in mind; we want to make it easy for them," said Dickins. "From a clinical perspective, Ezy-As provides minimal, to no, disruption to any injury or dressing."

The single-piece design requires no assembly and Dickins says it's easy to clean. The Ezy-As is made of lightweight plastic, which is durable and small enough to pack in a suitcase. It currently comes in three sizes, but the company is looking at developing an extra-large size to assist bariatric patients and those with significant edema. For those patients who need additional assistance, a handle attachment is also available to help self-application of lower limb compression garments. The handle is designed to remove excessive hip and knee flexion when donning a stocking. It also eliminates the need to plantarflex (toe point) the ankle to get the toes into the foot section of the stocking. The handle attachment fits all three sizes of the Ezy-As applicator.

The Ezy-As retails for between $39.95-$49.95, depending on the size, and the optional handle attachment costs about $25.00. Ezy-As products are available online at www.ezyasabc.net. East Coast Innovative Concepts based in York, Maine is the regional distributor; contact John Shusta at (207) 351-1487, or visit www.eastcoastinnovativeconcepts.com.

Concerned about your vein health?

Contact the Vein Healthcare Center for an evaluation.

Contact Us