Cover Story

New Alternatives: Non-Thermal Non-Tumescent Techniques in Vein Treatment

By Jennifer Boggs | Feature

Our legs are comprised of a network of veins that are similar to branches on a tree: they contain large, or major veins, and increasingly smaller veins. Healthy veins carry blood from all extremities back to the heart.

In the legs, blood is usually traveling against gravity, thus the valves in the leg veins perform an important function. Venous insufficiency, or vein disease, occurs if the valves in the veins become damaged and allow the backward flow of blood in the legs towards the feet instead of towards the heart.

When blood cannot be properly returned to the heart through a vein, the blood can "get backed up" or pool in the feet, leading to a feeling of heaviness and fatigue, causing congestion that will result in varicose veins and other skin changes. Over time, this increased pressure can cause additional valves to fail. If left untreated, it can lead to leg pain, swelling, ulcers, and other health problems.

Proper treatment means evaluating a patient's complete venous system, so that poorly functioning veins can be identified and treated at the source. Endovenous thermal ablation uses laser energy or radio waves to create an intense localized thermal reaction in the incompetent vein. The thermal energy causes vein to seal shut, stopping the healthy blood flow from entering the damaged vein. This keeps the blood flowing toward the heart, not allowing it to change directions and return to the feet. The body will reabsorb the damaged and treated vein, forcing the blood to be diverted to healthy veins in the leg.

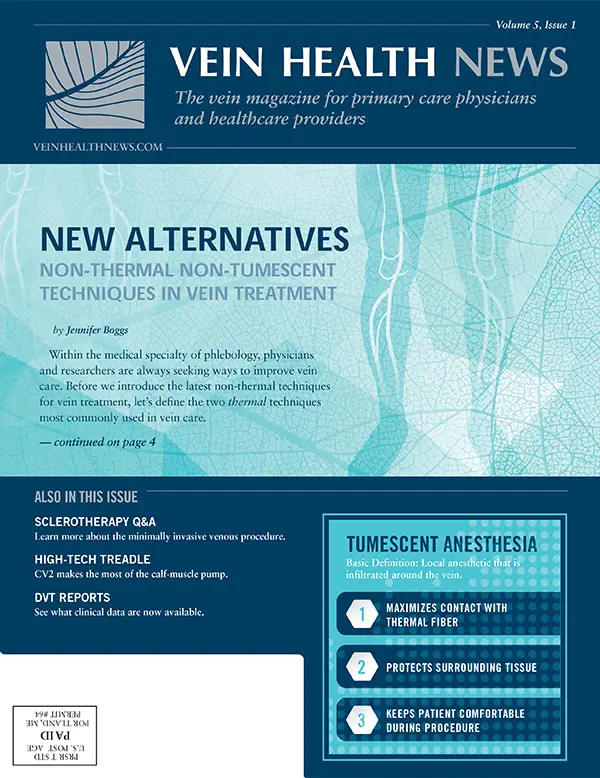

Endovenous thermal ablation, using laser or radio frequency, is an outpatient, minimally invasive procedure performed with local anesthetic. It is considered the gold standard in treatment of the great and small saphenous veins, two veins that are often the source of other lower extremity varicosities. Part of the treatment involves tumescent anesthesia, a technique in which a high volume of a dilute local anesthetic is infiltrated around the vein.

Tumescent anesthesia serves three purposes during endovenous thermal ablation. First, the fluid causes the vein walls to collapse around the thermal fiber maximizing contact. Second, the fluid creates an insulating ring around the vein and thermal energy source. This protects all surrounding tissues, including nerves and muscles, thus stopping any type of collateral damage. The third function is as an anesthetic, keeping the patient comfortable during the procedure.

The tumescent fluid can be introduced in a variety of ways but at the hands of some physicians, the process can be very uncomfortable. Additionally, if there is epinephrine in the mixture, it can cause tachycardia and other unpleasant feelings of anxiety. Non-thermal, non-tumescent (NTNT) modalities are newer procedures that do not require the use of tumescent anesthesia. The most talked-about NTNT techniques are currently chemical ablation, mechanico-chemical ablation (MOCA), and cyanocryalate adhesives.

Standardized compound makes for safer foam

Sclerotherapy isn't a new treatment for treating troublesome veins. (Primitive versions of injecting a substance into veins to seal them up have existed since as early as the 17th century). Modern day sclerotherapy is a process in which a medicine is injected into the vein causing it collapse and seal itself shut. The body will then reabsorb the vein into local tissue, in effect making the problematic vein disappear, shunting the blood into the healthy collateral veins.

Foam sclerotherapy has been widely used in the Phlebology community in the past ten years. The "Tessari method" has been the most common technique for producing foam for use in sclerotherapy. This technique involves manually mixing a small volume of liquid sclerosant with a volume of room air or other gas using two syringes and a three-way tap, or stopcock. Preparations created this way are referred to as "physician compounded foam."

While physician compounded, non-proprietary foam is inexpensive to make, medical experts caution that there are risks: there have been a number of published cases of micro-air emboli (small bubbles of gas in the bloodstream) from so-called "homemade foam" leading to neurological events in patients, including migraines, vision changes, strokes, and death. No physician-compounded foam has been approved by the FDA.

In 2013, the FDA did approve Varithena, a chemical foam solution indicated to close the Great Saphenous Vein (GSV) and related tributaries. It is a proprietary mixture of 1% polidocanol, 65% oxygen, 35% carbon dioxide, and less than .8% of nitrogen.

Dr. Robert Diamond, Vice President of Medical Affairs at BTG, the company that manufactures Varithena, explained what makes their product unique. "When a physician creates his own foam, he uses room air, which can contain as much as 78% nitrogen—compared to Varithena, which has extremely low nitrogen," he said. "While oxygen and carbon dioxide are rapidly absorbed into the blood stream, nitrogen is very slowly absorbed and those bubbles can persist and possibly cause a gas embolism and obstruct an important blood vessel."

Varithena's primary safety feature is the consistency of its bubbles: each one is between 100-500 microns, with uniform density and stability—a standardized compound that is much more predictable for vein doctors to use on their patients, especially when compared to physician-compounded foam, which isn't subject to any manufacturing standards.

The company also goes to great lengths to standardize the use of Varithena, meticulously training every physician who plans to use it. According to Anastasia Mironova, Vice President Marketing at BTG, clinically certified representatives conduct in-person training sessions about all aspects of the Varithena procedure. In addition, every Varithena sales representative must complete a rigorous certification process.

As more physicians in the U.S. have begun to administer Varithena to their patients, not all insurance companies have agreed to cover the cost, though that is changing. "BTG has a team of people whose sole purpose is to grow coverage for Varithena, and they have made considerable progress with payers in the 18 months," said Mironova. "Seven of the top ten commercial payers cover Varithena, as well as 22 of the top 25 'Blues' plans. With over 165M lives covered, BTG is leading the way in reimbursement for the entire NTNT category."

Device uses unique design to deliver medicine

The ClariVein® Infusion Catheter (ClariVein-IC) is a system designed to introduce physician-specified agents into the peripheral vasculature. Developed by interventional radiologist Michael Tal, M.D. and John Marano, PhD (both co-founders of Vascular Insights, the company that manufactures ClariVein), the device was cleared by the FDA in 2008 for the infusion of physician-specified agents in the peripheral vasculature.

The ClariVein-IC is designed with a 360-degree rotatable fluid dispersion wire connected to a battery powered motor drive unit. The catheter is introduced through a microintroducer at a single location, where the catheter sheath is navigated through the vein to the treatment site using ultrasound imaging. Physician-specified fluid is then delivered through its infusion port, surrounds the dispersion wire, and exits via an opening at the distal end of the catheter. The delivery of the fluid is enhanced by the use of the rotating dispersion wire to mix and disperse the infused fluid in the blood stream and on the vessel wall. In other words, the rotating inner wire agitates the epithelial lining of the vein, and when the fluid is sprayed from the tip of the catheter as it is pulled back, coverage is thorough and the effectiveness of the fluid is increased.

Many phlebologists are excited by the development of the infusion catheter and have described the use of it as "mechanico-chemical ablation" (MOCA) in their research. Currently, however, the only FDA-approved device that stimulates the endothelium of a vein while introducing medicine is the ClariVein-IC.

Lindy McHutchison, MD, a physician at the Carolina Vein Center, has been using ClariVein in her practice for two years. She believes that there are a number of benefits to using the catheter in vein care. "Because there is no heat, you don't need a lot of anesthetic, plus you disrupt less tissue around the vein than in other treatments," said Dr. McHutchinson. "It is less painful, less inflammatory, and produces less swelling and bruising after the procedure."

Although ClariVein is still a relatively new device in the vein care specialty, several pivotal clinical studies using the ClariVein-IC system have been published, with data that compared with the results using EVLA methods. Insurance coverage for the ClariVein IC device varies by geography and insurance company.

Vein closure using cyanocryalate adhesives

Cyanocryalate, a kind of strong, fast-acting medical adhesive, has been used in the treatment of blood vessel abnormalities (arteriovenous malformations) for over a decade. In February 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the VenaSeal Closure System, which uses a medical adhesive made from cyanocryalate to permanently treat varicose veins in the legs.

The VenaSeal system is made up of an adhesive, a specially formulated n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate, and delivery system components that include a catheter, guidewire, dispenser gun, dispenser tips, and syringes. During the procedure, the physician fills a syringe with the medical adhesive, and then inserts it into a dispensing gun attached to an application catheter. Using ultrasound imaging, the doctor inserts the catheter through the skin into the diseased vein to allow injection of the VenaSeal agent, a clear liquid that polymerizes into solid material. The catheter is placed in specific areas along the diseased vein and the physician conducts a series of trigger pulls to deliver the medical adhesive, thus sealing the incompetent venous valve shut and eliminating reflux. Compression is applied to the leg during the procedure, according to the indication for use by the FDA, but since it is not required post procedure, VenaSeal is an attractive option for patients who cannot tolerate compression stockings.

Medical technology company Medtronic launched the VenaSeal closure system in the U.S. in November 2015. Currently, it is the only non-thermal, non-tumescent, non-sclerosant procedure approved for use in the U.S. (It is also available in international markets, including Hong Kong, South Africa and the United Arab Emirates.)

According to Mark A. Turco, MD, Medical Director of Medtronic Aortic and Peripheral Vascular, VenaSeal closures are performed in a minimally invasive outpatient procedure and produces minimal-to-no pain or bruising. "The procedure is designed to minimize patient discomfort and reduce recovery time." said Dr. Turco. "Unlike other treatments, VenaSeal does not require the use of tumescent anaesthesia, minimizing the need for multiple needle sticks as compared to ablation procedures—and patients may not need to wear compression stockings post-procedure, although some patients may benefit from wearing them."

In terms of paying for the VenaSeal, no insurance companies currently covers the procedure, and patients must pay out of pocket at this time.

Transforming current care

The current standard of care for venous insufficiency is vastly superior to the traditional surgical approaches they have replaced. Thermal ablation procedures have all the usual advantages of minimally invasive techniques over vein stripping—lower anesthesia requirements, faster recovery, lower risk of complication—and are very effective treatments. But, said Dr. Robert Worthington-Kirsch, Chairman of the American College of Phlebology CME Committee, "they aren't perfect."

According to Kirsch, MD, FSIR, FCIRSE, FACPh, RVT, RPVI, tumescent analgesia is probably the least pleasant component of these therapies, and probably accounts for much post-procedure bruising and discomfort, at least in the short term. Dr. Kirsch has studied and considered non-thermal ablation techniques and their place in phlebology for some time. "The emerging non-thermal techniques have the potential to make treatment of saphenous vein disease even less invasive, with much improved patient experiences," he observed. "If they prove to be effective and durable therapies, non-thermal ablation may be as transformative and disruptive to the current care of superficial venous insufficiency as thermal ablation has been to conventional surgery."

RESOURCES

- VARITHENA: T King, MD, et al. Efficacy and Safety Study of Polidocanol Injectable Foam for the Treatment of Saphenofemoral Junction (SFJ) Incompetence (VANISH-1). European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2015;50:784-793.

- Todd KL. The VANISH-2 study: a randomized, blinded, multicenter study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of polidocanol endovenous microfoam 0.5% and 1.0% compared with placebo for the treatment of saphenofemoral junction incompetence. Phlebology. 2014 Oct;29(9):608-18. doi: 10.1177/0268355513497709.

- CLARIVEIN: S Elias, Raines JK. Mechanochemical tumescentless endovenous ablation: final results of the initial clinical trial. Phlebology. 2012 Mar;27(2): 67-72. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2011.010100

- Boersmaa D, et al. Mechanochemical Endovenous Ablation of Small Saphenous Vein Insufficiency Using the ClariVein® Device: One-year Results of a Prospective Series. European Journal of Vasc and Endovasc Surg. 2013 Mar:45(3):299-303.

- VENASEAL: T Lane, et al. Cyanoacrylate glue for the treatment of great saphenous vein incompetence in the anticoagulated patient. Journal of Vasc Surg. 2013 July:1(3):298-300.

- N Morrison, et al. Randomized trial comparing cyanoacrylate embolization and radiofrequency ablation for incompetent great saphenous veins (VeClose). Journal of Vasc Surg. 2015 Apr:61(4):985-994

Insurance

What's New With Vein Care Coverage?

By Vein Health News Staff

As vein care continues to advance, does health insurance evolve along with it? To find out, Vein Health News spoke to AJ Riviezzo and Cheryl Nash of American Physician Financial Solutions, LLC, a medical billing and consulting company that supports phlebology practices.

What is the billing procedure for patients who receive vein treatment?

New vein technologies are billed in roughly the same manner as and more established treatments, although newer treatments do not have specific CPT codes established at this time. [Current Procedural Terminology codes are those designated for medical procedures and services.] The services are reported to the insurance with the appropriate code(s), and medical records are often sent upon request. The claim should pay after review, though the patient may be responsible for a portion of the cost.

How do newer modalities receive insurance codes?

Many of the newer technologies are considered "experimental and investigational" and not yet covered by insurance, even though they have FDA approval. Adoption of new technologies by the insurance payers is usually a slow process. Advocacy by physicians and patients frequently help these technologies gain approval.

Are the companies who make these newer treatments doing anything to accelerate new codes?

We have heard that BTG, the manufacturer of Varithena, is seeking a CPT code. They have been working with many key payers to gain coverage for their product. VenaSeal from Medtronic is, at this time, a private pay product only. They are not seeking a CPT code, and they do not recommend billing this product to insurance.

What advice would you give to patients seeking insurance coverage?

In most cases, vein care offices work directly with the patient's insurance carrier to obtain approval or authorization for the patient's venous treatment. But patients should always check with their individual insurance companies to determine which treatment options are covered. The largest impact to patients over the past few years has been the development of the various Affordable Care Act plans. Many of these plans have high deductibles, which some patients may not realize. Additionally, healthcare networks for ACA plans have been reduced in some cases, which impact the patient's choices in care. Patients should educate themselves about their insurance policies, deductibles, and co-payment expectations.

Q & A

Sclerotherapy Q&A

By Jennifer Boggs

Patients often have common questions about sclerotherapy, a minimally invasive procedure used to treat spider veins and varicose veins. To shed some light on the topic, we spoke with Alison Scheib, PA-C from the Vein Healthcare Center in South Portland, Maine. An active member of the American College of Phlebology, she has a strong background in family medicine training, as well as specialized training in sclerotherapy and vein health.

WHAT IS SCLEROTHERAPY?

Sclerotherapy is a series of injections into a dysfunctioning vein; the provider uses very small needles to inject a medicine called a sclerosing agent into the vein's interior wall. This substance causes the vein to become sticky and seal shut, causing the troublesome vein to disappear. Blood then finds a healthy path back to the heart. "Ultrasound guided" or "light assisted" defines how the vein is visualized during these injections.

CAN YOU EXPLAIN THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ULTRASOUND GUIDED AND LIGHT ASSISTED PROCEDURES?

Ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy uses ultrasound to locate veins that are not readily visible and cannot be seen with a light. This procedure is often used to treat perforator veins, or veins that connect the superficial system (above the muscles in your leg) to the deep system (veins under and between the muscles of the leg). During light-assisted sclerotherapy, a small, hand-held light illuminates the veins and tissue directly below the skin, which allows the sclerotherapist to clearly identify the source of the dysfunction.

WHO IS THE IDEAL CANDIDATE FOR SCLEROTHERAPY?

Liquid sclerotherapy works best for those with superficial veins that are not directly connected to deep veins by junctions and have a diameter less than 5 mm. It can also be highly effective in patients who have leg symptoms such as heaviness, aching, pain, itching, swelling, throbbing, or skin discoloration or breakdown.

HOW LONG DOES THE TREATMENT TAKE? HOW MANY TREATMENTS DO MOST PATIENTS NEED?

Number and length of each treatment varies from patient to patient. Each session can take between 15 minutes and one hour, depending on the complexity of vein patterns and reflux. Most patients need multiple treatments (3-6 sessions, on average), however, there will be improvement with each session.

WHAT SHOULD SOMEONE EXPECT RIGHT AFTER SCLEROTHERAPY?

Immediately following the procedure, there may be mild itching of your legs. It typically resolves within an hour. For the next few days, there may be some tenderness and bruising. About two weeks following the procedure, you may feel hard bumps in the area of the treated vein, which usually disappear over the course of several months.

HOW WILL THE LEG LOOK OR FEEL A WEEK AFTER SCLEROTHERAPY? A MONTH?

Usually, the changes noticed in the first two months are improvement in symptoms. Patients have reported to me that their legs feel lighter, or without pain. The large, lumpy veins slowly disappear, usually 2-6 months after the procedure, and the smaller veins may disappear over the following six months. It's good to remember that as the veins resolve, there may be some color changes in the skin; legs sometimes look worse before they look better. But when they look better, they look great!

ARE THE RESULTS OF TREATMENT WITH SCLEROTHERAPY PERMANENT?

Yes, once the vein has collapsed, it typically gets reabsorbed into the body and is permanently gone. Because that vein no longer exists, it cannot cause problems in the future. That said, all the veins in the body have the same genetic makeup and have generally been exposed to the same environmental stresses and, in theory, have the same risk of failing. In other words, if a patient has one bad vein, it is likely that at some point they will have other bad veins. It's important to note that small, healthier lifestyle changes can make a big difference in managing chronic venous issues and preventing future problems.

CAN YOU GO TO WORK AFTER TREATMENT? WHAT ABOUT EXERCISE?

Yes, you can go to work after treatment. However, you should avoid heavy lifting and strenuous physical activity while standing for the first five days following sclerotherapy. Walking is great exercise after treatment. In fact, walking 30 minutes a day is a post-op requirement!

WHAT ARE THE MOST COMMON SIDE EFFECTS AFTER TREATMENT?

The most common side effects are bruising and tenderness of the treated veins. The bruising is usually fully resolved within two weeks and the tenderness responds well to heat and elevation. I do want to add that patients who follow the post-procedure guidelines for care will help promote the most effective healing. After each sclerotherapy session, compression stockings should be worn for 7-14 days, depending on the severity of the venous disease.

WHAT IS THE ONE QUESTION THAT PATIENTS ASK YOU THE MOST?

"Will it hurt?" Everyone's experience is different, but most people describe it as quick little bee stings. It is always possible to stop the procedure or take a break if someone does find it very uncomfortable, but most patients say it is very tolerable. The medicine is pH balanced and vein access is with a 27-32g needle, so it's really just a very small perceivable pinch.

HOW MUCH DOES SCLEROTHERAPY COST AND DOES INSURANCE COVER IT?

Costs vary, but it's usually about $300-$500 per session based on how the vein is visualized (light-assisted vs. ultrasound). Insurers describe sclerotherapy as an "adjunct" procedure and may cover it in part or in full if a bigger procedure has been done in the past, such as radiofrequency or laser ablation, or if there is an open ulcer. Patients should work with their treatment provider to understand their health insurance coverage.

Patient Perspective

One Patient's Perspective: By The Book

By Benjamin Lee

Lucille Laliberte recently celebrated her 69th birthday and her legs feel better than when she was 68. Varicose veins run in her family (her dad and uncle had them) and she suffered from them too.

In addition to heredity, environmental factors were also at play. Lucille retired from federal work at a veteran's hospital in 2007, but prior to that she'd been in the Coast Guard for 14 years. She spent many of those years on merchant ships, climbing up and down steel ladders to inspect the inside of fuel oil tanks. Wearing men's size steel-toed safety shoes didn't help. A family history of venous disease combined with demanding work conditions set the stage for Lucille to develop varicose veins.

"I've had varicosities all my life," said Lucille. "I live on the second floor and walking up the stairs, or even sitting for too long, my legs would feel very heavy and tired."

Lucille began the process by doing research online. She found the Vein Healthcare Center's website and read over the information in great detail. When she went to her initial evaluation, she was pleased to discover that the staff, sonographer and doctor were just as thorough with information as the practice's website.

Lucille's sonogram revealed that she had faulty vein valves in both legs. She had the endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) treatment for her right leg, and then two weeks later had the same procedure performed on her left leg. She described the EVLA as "comfortable" and was glad that the doctor explained everything that was happening throughout the procedure.

After the treatment on her right leg, she noticed a reduction in swelling the very same day and could see the outline of the muscles in her leg for the first time in a long time. Her legs and feet felt "lighter" right away, and her legs stopped itching too. Lucille is grateful to have had saphenous vein incompetency of the "plain vanilla" variety, with no unusual issues or complications. The post-procedure process also went smoothly, and any bumpiness or discoloration on her legs resolved quickly—something Lucille attributes to her compliance to the post-op instructions.

"Everything fell back into place fairly quickly, because people who follow their doctor's instructions tend to do better!" she said.

She said that compression stockings were challenging for her because of difficulty in getting the right fit. Regardless, she understood that they're "well worth wearing" and used them "religiously." Another thing that Lucille did unfailingly was to walk for 30 minutes daily to help her legs recover. She enjoyed it so much that she kept it up, even through the winter months. Now she walks at least 30 minutes a day, usually more. Even her primary care physician has noticed the difference in her health and is pleased that she's kept up the walking.

Lucille is relieved to have taken care of her legs before they got worse and encourages others her age to consider it.

"If it had been a superficial or cosmetic procedure, Medicare wouldn't pay for it, but this was a medical necessity" said Lucille. "Anyone that's bothered by varicose veins should have it done, because you can't do much if you're legs aren't healthy."

Vein Tech

CV2

By Jennifer Boggs

All day long, the human circulatory system is moving blood to every cell in the body—the heart pumping oxygen-rich blood to the arteries, the veins taking the deoxygenated blood back up to the heart, where it is pumped directly to the lungs which replace the carbon dioxide with oxygen, and the process continues.

In the legs, blood returning to the heart is usually traveling uphill against gravity, but if the valves in the veins become damaged and allow the backward flow of blood in the legs, then venous insufficiency occurs.

One simple technique to aide the venous return of blood to the heart is the "calf muscle pump." Repeatedly tapping your feet, going back and forth between heels and toes, squeezes the deep veins in the legs helps the valves in the veins direct the blood back toward the heart and encourages the blood to circulate through the leg.

A treadle is a foot-powered pedal or level used for circular motion, such as in a potter's wheel or sewing machine. The CV2 (named for the natural "second heart" of the calf pump) is essentially a treadle that uses momentum to keep the pedal—and the calf muscles—moving up and down for a long period of time and with minimal effort.

According to Jim Hundley, Jr., CEO of GO2, LLC, the company that makes the CV2, treadling for wellness likely started in 2004 when a physical therapist named Richard Hand was working with an elderly patient who couldn't perform prescribed rehabilitation exercises. Hand noticed that the patient had a sewing machine in her home and asked if she would be willing to try using the pedal if he removed the resistance belt. She gave it a try and after two weeks of treadling twice a day for fifteen minutes, she showed much improvement.

After repeated success with other patients, Hand worked with a design engineer to create prototypes of momentum-assisted treadling devices. Hand formed the Treadwell® Corporation, which received a patent for the devices in 2011. Soon after, GO2, LLC licensed the Treadwell® patent to develop and market an affordable home-use device that is relatively small and light in weight.

Treadling on a CV2 powers the calf muscle pump, but what's the difference between using the CV2 and doing a calf muscle pump without it? The CV2 enables patients to do the calf pump for longer periods of time, a benefit especially for those who have trouble walking or exercising. People who do the calf pump by repetitively dorsiflexing and plantarflexing their ankles soon quit because of the relative low endurance of the anterior compartment muscles. The CV2 takes over the dorsiflexion phase, allowing the user to keep the pedal going by only using the calf muscles (gastrocnemius and soleus muscles) to create gentle downward thrusts through the balls of the feet.

Another feature of the CV2 is that the pedal (unlike a sewing machine) is inclined such that moving the ankles up and down barely moves the knees or thighs. This allows the body to remain still, avoiding excessive up and down motion of the thighs, which can cause ischial bursitis.

In the area of vein care, published research has shown that treadling on the CV2 results in marked increases in venous blood flow velocities at the femoral vein and artery, as well as reduced leg volumes and reduced pain in those patients with edema. Hundley added that there are also reliable reports that treadling accelerates the healing of sores and ulcers, related to poor circulation.

The CV2, however, is not a treatment for acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and should not be used as such. Though prices vary according to seller, the cost for the CV2 is about $300. Physicians and patients can buy the product directly from the GO2 website (www.goodbloodflow.com), or by phone at 1-855-TREADLE.