Cover Story

Venous Ulcers: The Advanced Stage of Venous Disease

By Jennifer Boggs | Feature

Leg ulcers are not easy to live with. Open areas can be painful, difficult to heal, and the likelihood of recurrence is significant. Ulcers are as challenging to treat—but treatment is possible.

Venous disease is thought to account for approximately 80% of chronic leg ulcers. "Venous disease" refers to a range of conditions related to or caused by veins that become abnormal, from spider veins to large variscosities. Healthy vein valves open and close to assist the return of blood to the heart. Venous reflux occurs if these valves become damaged, allowing the backward flow of blood into the lower extremities. When blood pools in the lower leg over a long period of time, the result is often the transudation of inflammatory mediators into the subcutaneous tissues of the leg and subsequent breakdown of the skin tissue.

The exact etiology of venous ulcers is complex. Though incompetence of vein valves is closely correlated with the development of venous ulcers, precisely how it develops into ulceration is unclear. Many theories exist that can explain the predictable process. What is certain is that venous ulcers are an indication that venous disease has reached an advanced stage.

Diagnosing differences

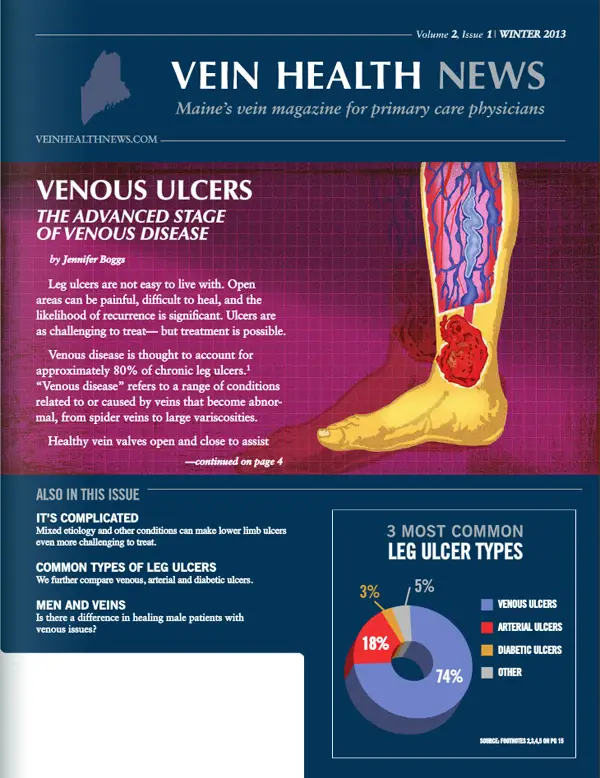

There are three common types of leg ulcers: venous, arterial and diabetic. While venous ulcers make up about 80% of leg ulcers, arterial and diabetic ulcers make up approximately 20%. According to Erich Fogg, PA-C, clinical appearance is the first clue to distinguishing between venous and arterial ulcers. Fogg, program director of the York County Center for Wound Healing and Hyperbaric Medicine at York Hospital, says the location of the ulcer is important. Typically, venous ulcers can appear anywhere between the knee and the ankle, while arterial ulcers are usually found between, or on the tips of, toes.

Discoloration is another sign. Venous-related wounds tend to be ruddy, and the surrounding tissue may be red or hyper-pigmented due to hemosiderin staining. In contrast, the wound bed of an arterial ulcer tends to be black, grayish, or yellow. The most effective way to diagnose a venous ulcer is with a duplex Doppler ultrasound, which reveals whether or not the blood is flowing in the proper direction, or if there is any pooling occurring.

"With any wound, we want to make sure that we've identified the right etiology," said Fogg. "Though ulcers may appear similar, each one has a different cause and thus, very different treatments". In addition to a physical exam, health history plays a role in diagnosing the type of ulcer. Though it's long been believed that venous disease is hereditary, we know that environmental factors play a role in the expression of a possible, as-yet-unidentified, gene that is associated with venous disease. Living in a westernized country carries a higher risk of developing venous insufficiency.

Treatment and management

Fogg and his colleagues thoroughly clean each wound so no bacteria is present that would impair healing. They remove any non-viable tissue then apply the appropriate dressing based on the clinical appearance of the wound. (If a wound is very wet, for example, they apply a dressing that wicks away drainage). Initial treatment is immediately followed by aggressive compression therapy. Again, it is critical to distinguish these two types of ulcers, because compression stockings, used in treating venous ulcers, can actually make arterial ulcer worse. Another treatment modality is human cultured skin grafts, a technique that has been utilized for almost 15 years.

Dr. Walter Keller, medical director of the Mercy Wound Healing & Hyperbaric Center in Portland, often uses a combination of modalities to heal patients' wounds, including skin grafting and "low-tech" therapies like elevation. Venous ulcers are the most common wounds treated at the Center, accounting for almost 80% of the work they do. Dr. Keller believes that the biggest misconception among physicians is that there's nothing you can do for venous ulcers. "We can treat and even heal the wound, but unless the underlying cause is addressed, it will only reoccur," he said. One well-cited study supports that: up to 50% of venous ulcers re-occurred by the fifth year after healing.

Whether the ulcer is open or healed, a vein specialist can step in to treat the cause at its source: the venous system. Dr. Keller often refers his venous ulcer patients to a phlebologist for endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) or radio frequency therapy of the saphenous vein. "In the old days of vein stripping, patients were out of work for a week and had a bunch of incision scars," said Dr. Keller. "I think what the family practitioner needs to know is that modern therapies are minimally invasive, non-surgical and provide excellent outcomes and overall healing for patients".

Fogg concurred that treating the incompetent vein valves that contribute to venous ulcers is key for lasting results: "For long-term management, we attempt to identify if there's any anatomical lesion, or if it is a vein that is problematic. If it's the vein, we refer our patients to a specialist for intervention". He added that the earlier the intervention and treatment, the better chance a wound has to heal and stay closed.

Preventing ulcers

There are warning signs that a patient may be developing a venous ulcer. Noticeable skin changes in the lower legs, such as dryness or thickening, is one sign. Fogg suggests helping patients to protect the affected area by maintaining a good moisture balance. Another sign of possible ulceration is discoloration of the legs, typically dark red, purplish, or a brown, woody appearance. Other possible indications are aches or pains in the legs, especially when standing or sitting for prolonged periods.

Dr. Keller cited varicose veins as a possible warning sign. Varicose veins, as with any form of venous disease, are often hereditary. If a patient has varicose veins or a family history of varicose veins—he or she should be evaluated and treated for them before they lead to ulceration. Risk factors for venous ulcers include older age, a history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), venous insufficiency, and previous ulcers or leg injury. "You can't change your genetics, but there are modifiable factors," said Fogg. "For example, wearing compression stockings to promote circulation if a patient has a job on his or her feet all day".

COMPLICATIONS WITH VENOUS ULCERS

Lower limb ulcers are anything but straightforward, and there are some conditions that can complicate matters even further. Mixed etiology of venous ulcers is one example. Several studies have shown that many ulcers have more than one etiology. In one study out of 689 limbs, 100 (14.5%) had developed ulceration from mixed arterio-venous etiology and 11 limbs (1.6%) from mixed lymphedema and venous disease.

Like other ulcers, those with an arterio-venous etiology may develop on the calf or foot. Healing requires correction of arterial insufficiency—a lack of enough blood flow through the arteries—which is typically caused by atherosclerosis. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis who present with limb ulcers, have a 50% chance of having arterial or venous contribution.

If the ulcer is venous and diabetic, the patient should have a venous evaluation after the blood glucose level is controlled to the best of the patient's ability. Though blood sugar control is imperative for health, the ulcer can be encouraged to close with venous intervention. This helps a patient return to an activity level that can actually help keep the diabetes under control.

If the ulcer has a mixed arterial/venous etiology, it is more complex. In this case, timing and treatment truly depend on the severity of the arterial disease. If the patient is a candidate for a bypass surgery, it is possible to remove the vein in a more traditional manner—namely phlebectomy—so it can be used as a graft, essentially fixing two problems at once. However, if the patient is not a candidate for bypass and is told to increase exercise, sometimes treating the venous component can help the patient have less diffuse heaviness and aching in his legs allowing an increase in daily activity.

Dermatitis is a common complication of venous ulcers. The skin surrounding the wound is often scaly, weeping and crusting and can be intensely itchy. If the dermatitis isn't treated, it may lead to further ulceration. A possible complication of a non-healing ulcer is osteomyelitis, or infection of the bone (or bone marrow) caused by bacteria or other germs. One of the worst-case scenarios for untreated long-term venous ulcers is when the lesion becomes malignant. Though rare, aggressive ulcerating squamous cell carcinoma—known as Marjolin's ulcer—is very difficult to treat.

Working together

Both Fogg and Keller agree that, as with all patients, venous ulcer patients are best managed by a multi-disciplinary approach: primary care physicians, wound care centers, and professionals that have expertise in venous care. Working in conjunction can take various forms. Sometimes a phlebologist will treat a patient who has wounds that won't heal; other times a wound healing center will send a patient to a phlebologist to treat the incompetent vein valves that are contributing to the ulcer. In any case, early intervention is essential to healing rates and preventing future ulcers.

Although the goal of wound centers is to heal wounds, ulcers can be chronic conditions that aren't necessarily cured but managed, according to Fogg. Many patients must manage their conditions for the rest of their lives. His goal is to heal wounds once and for all. In fact, when he discharges a patient, he'll often say, jokingly, "I hope I never see you again". Fogg added one caveat: education about compliance and follow-up care is important. If patients are motivated and compliant with their therapy, there is less chance they'll need to return. But, said Fogg, "it's hard for patients to comply, so it's not uncommon to see them come back".

Men's Health

Men and Veins

By Benjamin Lee

According to epidemiologic studies of the 1960s and 70s, women are more likely than men to have venous disease, including varicose veins and spider veins. More recent research shows, however, that this may not be the case. We also know that men are more likely to suffer from vein issues and tend to present with the worst vein problems, such as ulcers. Why is this the case?

Phlebologists have often observed that women tend to get help for their vein issues right away, while men will often wait until the problem becomes too painful to ignore. The result is, more often than not, leg ulcers that are difficult to heal. Even men who are athletic are susceptible to venous disease. Sometimes men with vein problems misinterpret their symptoms, mistaking the pains of venous disease for a strained or pulled muscle.

The important thing for patients with vein issues is to seek help as soon as symptoms present themselves, regardless of his or her gender. Venous conditions like varicose veins get worse with time, and the longer one waits, the more extensive the condition could become—and often, the treatment. Anatomically, men's leg veins are no different from women's veins. Looking at a leg ultrasound, one would be hard-pressed to tell the difference between a man's and a woman's legs.

The key for male patients, in particular, is to get evaluated as soon as the symptoms become apparent. Common symptoms of venous disease include:

- LEG FATIGUE OR HEAVINESS: When legs feel good upon waking but are intensely tired or heavy at the end of the day, this is an early warning sign.

- SWELLING: Swelling can be caused by many things but also serves as a very early warning sign for vein problems. In any case, legs that frequently swell shouldn't be ignored.

- SKIN CHANGES: Redness, skin thickening or other color changes on the legs and/or ankles is a common (and commonly overlooked) symptom. Other skin changes, such as dermatitis, cellulitis, dry or scaly skin, or brown "stains" on the skin can be signs of advanced venous disease, and should be evaluated by a physician.

- SPIDER VEINS: Spider veins are blue or purple-colored veins that occur under the skin but are close enough to be seen on the surface. Treating them can improve appearance, as well as stop the progression of venous disease at its source.

- VARICOSE VEINS: Another sign of early stage venous disease, varicose veins are visible veins in the leg that bulge, often protruding through the skin.

- ULCERS: An open wound on the leg or ankle that fails to heal can be the result of ongoing venous disease. In fact, "venous ulcers" in the leg are often an indication that venous disease has reached an advanced stage.

Venous disease is a progressive disease that is not curable, but for most people, even debilitating symptoms are completely treatable. Today's vein treatments are done on an outpatient basis and are minimally invasive and nearly pain-free. Treatment can stop the progression of venous disease and its complications for those in all stages of the disease, however, early intervention is generally best-tolerated and provides the most improved quality of life. For those struggling with late-stage symptoms, it is still possible to restore health.

Patient Perspective

One Patient's Perspective: An Educational Experience

By Benjamin Lee

Joshua Burkett is a chef. Years in the restaurant business have kept him on his feet for extended periods of time, which—combined with a family history of varicose veins—was a recipe for unhealthy legs. "I started getting varicose veins in high school, but as unsightly as they were, they never really bothered me," said Burkett. As the New Hampshire native got older, his veins got worse. They continued to get bigger and stay swollen for longer periods of time. Even crawling on the floor with his young kids was hard because of the varicose veins on his knees. But the self-proclaimed "tough guy" continued to live with the discomfort.

When he was about 27 years old, however, he started to experience undeniable medical issues. The skin covering Burkett's veins gradually got thinner and thinner, especially on the insides of his ankles. Eventually the skin got so thin on the inside of his right ankle that it ruptured and began spraying blood "like a squirt gun coming out of the side of his foot," as Burkett described it. "It was scary. I didn't know what to do, so I rushed to the emergency room where they gave me a Novocaine injection and stitches that stayed in for a week," he said.

That was the first emergency. Ten months later another bleeder opened up higher up on Burkett's right leg. He began to take the problem seriously and went to two different doctors for treatment. One physician encouraged vein stripping. The other physician advised against it but offered no alternatives. Burkett was confused: "I never really had a clear path of what to do". Finally, Burkett found his way to a certified phlebologist. An ultrasound revealed the source of the problem, and Burkett worked with the new physician on a treatment plan. He proceeded to have endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) on his right leg first, followed by his left leg two months later. The phlebologist followed both EVLA procedures with sclerotherapy. As Burkett put it, the EVLA "dams up the river," and then the sclerotherapy gets rid of the other streams leading up to it.

Burkett was nervous before the procedures, but found that it was a lot easier than he expected. The most difficult part of the experience has been the compression stockings required after any vein procedure. Though he admits the compression makes his legs feel better and more comfortable, it's more than a little unpleasant to wear them in a hot kitchen. He strongly suggests that anyone who has to wear compression to get their garments professionally measured and tailored, because otherwise "you're battling with them all day".

Burkett's goal was to restore healthy venous return in his legs, but he's been surprised by how much more comfortable and confident he feels. "I'm not as apprehensive about wearing shorts and showing off my legs now, because before they were gnarly and bumpy," said Burkett. "They're not Tom Brady's legs yet, but they look much better than they did". Overall, the experience has been an educational one for Burkett. Once he really understood what varicose veins were and what his specific problem was, he couldn't wait to fix it. In fact, he wishes a vein exam could be part of every general physical. "It's a quick thing to look at someone's legs to see if there are varicosities. There are a lot of possible treatments, and the earlier you start the better off you are".

FAVQ

Is Restless Leg Syndrome vein-related?

By Dr. Cindy Asbjornsen

Is Restless Leg Syndrome vein-related?

The short answer is that we're not exactly sure. In fact, a single unifying cause of Restless Leg Syndrome (RLS) has yet to be established. We do know is that there are many potential causes for RLS, including pregnancy, diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis, not to mention medications such as antihistamines, anti-depressants, and a certain class of high blood pressure medicine. RLS is considered a disruptive neurologic disorder, affecting approximately 10 percent of the U.S. population. It occurs in men and women, though the incidence is twice as high in women. RLS is not diagnosed through laboratory testing, but rather through evaluation of symptoms.

About 40 percent of people with RLS have problems with their veins, but we don't fully understand the relationship between RLS and venous disease. Research shows that there is high correlation of patients who see their RLS resolve when they receive venous treatment. One study showed that treatment of venous reflux eliminated or significantly reduced 98 percent of a person's RLS symptoms. (Ninety-two percent of symptoms did not return after one year.) Despite this study and others, there are currently no prospective random clinical trials that show that RLS is directly related to veins.

It is worth adding that many phlebologists have found that when patients wear graduated compression stockings, their RLS symptoms improve. There is no cure for RLS, but many treatment options are available to help manage symptoms, including long-term use of prescription medication. In my own experience, I've had patients tell me that treatment for venous insufficiency has completely relieved their RLS and others who saw no difference at all. But research findings and anecdotal evidence suggest that the patients who are evaluated for restless legs syndrome would benefit from an evaluation for possible vein disease as well. An article in the journal Phlebology (2008;23:112-117), for example, concludes that all RLS patients should be properly evaluated for venous reflux before initiation or continuation of drug therapy.

Vein Tech

LympheDIVAs

By Jennifer Boggs

Six years ago, patients with lymphedema in their arms had limited options from which to choose; compression sleeves came in beige, beige or beige. The founders of LympheDIVAs sought to change that and now offer a variety of sleeves that are colorful, stylish and comfortable—and more likely to be worn.

Rachel Troxell and Robin Miller were two young breast cancer survivors who developed secondary lymphedema as a result of their breast cancer treatment. They were both prescribed compression sleeves to control the arm swelling, but every sleeve they found was heavy, coarse and unattractive. So, the pair met with a fashion designer, and LympheDIVA was created. After spending two years building the company, Troxell's breast cancer returned and she died in 2008, at the age of 37. Her brother Josh Levin now runs the company, along with their mother Judy Levin. Their father Dr. Howard Levin is the Chief Medical Officer.

"Rachel's mission was to help women manage the disease of lymphedema, which she felt was, in some ways, worse than her breast cancer," said Dr. Levin. "Breast cancer is hidden, but once you put on the prescribed sleeve, it's out there and everyone will ask, 'what's wrong with your arm?'"

Troxell was also a triathlete and wanted a medical compression sleeve that wicked away moisture like the garments she wore in competition. The resulting design was a sleeve with a fine knit construction for a lighter, smoother feeling, with "360-degree stretch" that prevents binding at the elbow. Another unique feature is an added unscented aloe vera microcapsules to protect the skin, which can be sensitive in lymphedema patients. Of course the most noticeable difference in LympheDIVAs' sleeves are the designs, which range from subtle floral patterns to more fashion-forward prints—everything but beige. The sleeves make a fashion statement, or as Dr. Levin put it, "medically correct fashion".

LympheDIVA makes two garments: compression sleeves, which control swelling from the wrist to the axilla, and gauntlets, which cover the hand and stop right below the second knuckle. Studies have shown that hand compression is an important part of lymphedema management: if a patient is only wearing a sleeve, the compression at the wrist can act like a tourniquet and prevent proper circulation in the hand. The company is currently developing a compression glove, which would incorporate compression within the fingers.

All garments are available in compression Class 1 (20-30mmHg) and Class 2 (30-40mmHg). Compression starts at the wrist, between 20-30 mm and then gets lighter as it goes up the arm. Although anyone can follow measurement instructions on the company's website, Dr. Levin recommends that patients get fitted by a professional. For the best fit, LympheDIVA created a tool to help physicians, therapists and fitters to measure patients for the most appropriate compression.

"Everyone's arm is shaped differently and come in a wide range of circumferences," said Dr. Levin. "We want to go further than off-the-shelf measurements and fit for points of compression, not just size". LympheDIVAs' garments can be used for any post-procedure that requires graduated compression, including veins treated in the arms. They can be found in retail locations in US and Canada, as well as online at www.lymphedivas.com. The average cost for color sleeves is $60-$65, comparable to other sleeves on the market. Pattern sleeves cost about $90. The company also offers deals for customers buying both sleeve and gauntlet. "I'm trying to continue what Rachel had started, to help women feel better," said Josh Levin. "We want to make medical devices that people will actually wear and not leave in the dresser".